You are here: Home

|

|

|

You are here: Home |

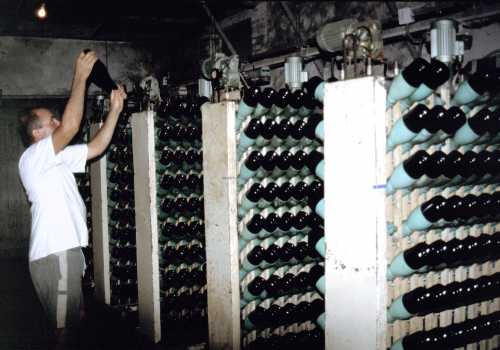

How to drink good Champagne on a tight budgetThis article was written for Living France magazine, and made it into the December 1999 issue by the skin of its teeth under the title Bubbly for the Millennium. Unfortunately it suffered severe cuts in the process, losing over 60% of its length and, I believe, much of its interest. Here is the full text, re-edited.  There’s an Englishman who farms in Normandy and has a stall at one of our wonderful local markets every week. Early this summer, having read some of my articles in Living France, he mentioned that a friend of his is a Champagne producer. Maybe I’d like to meet him and write an article about his wines... The following week he gave us a tariff and a bon de commande (order form) from F.Bergeronneau-Marion, propriétaire-récoltant (literally ’harvester’, but meaning ’grower’). The prices were very interesting indeed, with bottles ranging from 73 francs (about £7.70) for basic Brut and Demi-sec to 108 francs (£11.35) for Brut Millesimé 1988 - a vintage Champagne from an excellent year. Given that basic wines from the Grandes Marques (Moët et Chandon, Veuve Clicquot, Mumm and the rest of the 24 houses that have awarded themselves this exalted status) sell for at least £13 in French hypermarkets and well over £20 in Britain, and big-name vintage bubbly commands silly prices, we decided to investigate.  The full range of Bergeronneau Champagnes The bon de commande was printed on a postcard showing what was obviously the producer’s house - delightful, but hardly a château. This suggested a small-scale operation, probably quite traditional, which - along with the prices - could be specially interesting to us and to Living France readers. Preliminary research produced a surprise. Monsieur Bergeronneau’s home village of Villedommange doesn’t even rate an entry in the Guide Michelin, yet The New Sotheby’s Wine Encyclopedia prints a delightful Autumn view of it and lists it as a Premier Cru (first growth) village. This puts it in the top half of the rather complicated pricing structure for Champagne grapes, though not in the top 5% of Grand Cru ones. I phoned from Normandy to arrange an interview. Unfortunately Monsieur Bergeronneau was suffering from acute sciatica and couldn’t speak to me. A week later, he would be delighted to meet us so that we could taste and hopefully buy some Champagne for our Millennium celebrations, but he wasn’t sure he wanted to be the subject of an article. My French isn’t at its best on the phone, and he wouldn’t be the first vigneron to assume that an article by me was going to cost him serious money, so I sent him a carefully-composed fax. When I rang from Beaune the night before our planned visit, he was full of enthusiasm for the idea. Getting thereMy previous visits to Champagne had centred on the great cathedral city of Reims. This time we came through Épernay - an amazing drive past famous Champagne houses, each with its visitor centre from which happy tourists emerged clutching opulently printed carrier-bags full of precious bottles for which they had probably paid ridiculous prices. We took the N51 for Reims and paused for a hurried picnic lunch in the Forêt de la Montagne de Reims - an exciting few minutes trying to eat and drink in a violent thunderstorm while taking turns to hold a metal-shafted umbrella (the perfect lightning-conductor), much to the amusement of the French munching away in their cars. A left turn took us onto the D26 for Sermiers, and we picked our way through the tiny villages of Chamery, Ecueil and Sacy to Villedommange. Every village was full of Champagne producers, but unlike those in Épernay these were small independents. The approach by autoroute from Calais (about two hours on the A26) or Paris (an hour on the A4) is much simpler. The Reims-Tinqueux interchange - Sortie 22 on the A26 - will, with a bit of careful map and sign reading, get you onto the D980. Just after you pass through Pargny-lès-Reims, a left turn takes you straight to Villedommange. There were signs directing us to the Champagne producers in all the villages, and we had no trouble finding the home of Florent Bergeronneau and his wife Véronique, in a pleasant, almost suburban street that ended abruptly in a vast slope of vines.  Some of Monsieur Bergeronneau’s vines They welcomed us warmly. After a brief, courteous bonjour (with the kisses-on-cheeks that all young French children must offer adults, even strangers) from their two children (3½ and 6), we were invited to taste the Brut Grande Réserve (a princely 77 francs or £8.10 a bottle).  What do you say? We have tasted Champagnes we liked a lot, some we liked even more and some we liked quite a lot less, but we have never tasted one we didn’t like at all. The truth is that nobody in their right mind would make bad Champagne - the investment in equipment, effort, expertise, cellar-space and, above all, time (as you will see) is just too great. We liked this one quite a lot. So began over four exhausting but fascinating hours spent trying desperately to keep up with Monsieur Bergeronneau’s machine-gun French. His enthusiasm was not at all impaired by an obviously painful injury, supported by the ceinture (corset) which French doctors seem to give everyone with back problems. The pet projectHe is currently building a salon de dégustation at the bottom of his steep front garden. This will provide a more suitable setting than his rather cramped office for prospective clients to taste his wines. More important, he intends holding half-day initiations - four-hour tutorials in the appreciation of Champagne. These are being run between May and November by a number of vignerons with support from the Chambre d’Agriculture de la Marne and the Épernay tourist office. Visitors will start with directed tastings of things as varied as cinnamon, butter and pineapple - primary education for noses and palates. Then they will taste a range of Champagnes with different foods - ’le foie gras, par exemple,’ he said casually - and attempt to describe them,. The aim is ’the dissection of the elements of flavour’, not from an academic or technical point-of-view but with the sole aim of enhancing the taster’s enjoyment of these very special wines, whose characters are ’far more complex than those of red wines’ (I wonder if our freinds in the Vaucluse would agree!). We were given a sheaf of publicity leaflets and tasting notes full of the vocabulary of dégustation - old/young... flowery/fruity... eye/nose/mouth... profile (the sizes of the bubbles and how they rise in the glass)... body/spirit... heart/soul...  Most visitors will be charged for the initiations, but les bons clients will be admitted free. We hope to attend one and report back when the salon is open. This, we realised, was a man with a passion, and it took some determination to steer him onto more mundane matters. ’Un petit vigneron’Monsieur Bergeronneau is only a second-generation vigneron, but his wife’s family have been making Champagne for many generations. He started with just one hectare (2½ acres) of vines when the average for small growers was 1.8 hectares, but still managed to live, acquire a house and ’a good car’, and expand the business. At first his grapes were mixed with those of his fellow-members of the Villedommange coopérative - only the second of many that now exist in the Champagne region - but after 12 years he made an arrangement in which another vigneron pressed his grapes alone, allowing him to preserve the individual character of their juice. Now he has his own equipment for almost every step of the complex sequence of processes that turns simple grape juice into the world’s greatest sparkling wine.  At this point, our assumption that this would be a small-scale operation took a tumble. He had described himself several times as ’un petit vigneron’ - a small producer - but contradicted this with some impressive statistics. He now has 12½ hectares (over 30 acres) of vines, some from his own family, some from his wife’s and some bought as the business has grown. He produces a staggering 65,000 bottles of Champagne each year. Petit? It’s all relative. The 24 great houses produce an average of ten million bottles a year each. Some Bergeronneau grapes end up in Grande Marque wines because he sells freshly-pressed juice to the négociants (merchants) who supply the big producers. This is an important means of generating immediate income to cover running costs and for investment - essential when your own Champagne must be kept for between three and eight years before it is sold (the Grande Réserve we had tasted is sold at four years old). Unlike the still-wine producers I have described in previous articles, Champagne makers can’t sell their wine en vrac - it’s not the same without the bubbles! Very few foreigners, he told us, realise that small producers can make good Champagne, so outside France the great houses dominate the market. The French, however, appreciate the individual character of single-producer Champagnes. There are around 3000 individual producers in 300 villages throughout the region, and the Syndicat des Vignerons is working hard to promote their wines, which are already popular in France. Astonishingly, the Bergeronneaus employ only three people for most of the year, but this leaps to 43 during the vendange - the ten- to twelve-day picking season - with 40 pickers, two press-operators and a full-time cook to feed them all. Picking usually starts around the 20 September, but can be some weeks earlier or later depending on the capricious climate of the region.  ’Very hard work indeed!’The regulations for Champagne, laid down by the all-powerful Institut National des Appellations d’Origine, dictate that all grapes must be picked by hand - an awesome task with each hectare yielding 13,000 kilos of grapes! The Bergeronneaus grow all three of the permitted Champagne varieties: the black Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier and the white Chardonnay (Pinot Noir and Chardonnay also produce the great red and white wines of neighbouring Burgundy). Black grapes for white wine? Had we somehow missed out on red Champagne? No - red wine is made by fermenting lightly crushed black grapes before they are pressed, allowing colour to be extracted from the skins. If they are pressed very carefully before fermentation, the juice extracted is as white as that from white (or green) grapes. Champagne may be made from any or all of these varieties. Black grapes alone produce blanc de noirs and all-Chardonnay wine is called blanc de blancs. The small amount of still red wine produced each year from Pinot Noir, with up to 30% Pinot Meunier to give added fruit character, can be sold as Côteaux Champenois but is also used for blending rosé Champagne. Another INAO directive insists that about 20% of the still wine produced in the first stage of Champagne production must be held in reserve for blending in future years (the exact amount varies from year to year). This allows grapes from good years to improve wines made in more difficult ones. Bureaucracy gone mad? No. It makes life complicated, says Monsieur Bergeronneau, but is a good principle that ensures consistently high quality from year to year - very important when you are working in the most northerly, and climatically the most challenging, wine-region in France. This mighty organisation is also empowered to test and taste finished wines and to refuse to allow the sale of any that don’t come up to the required standard. With still wines this would simply mean downgrading the wine to Vin de Pays or Vin de Table status. With Champagne the bottles must be emptied and the wine must be blended and finished all over again - a mammoth task and a huge loss to the producer, so they make their wines very carefully and have them tested independently to ensure that they conform to the rules. All these controls, says Monsieur Bergeronneau, make the production of Champagne very hard work indeed, but it gives ’beaucoup de satisfaction’. You have to be a farmer, a technologist and - because Champagnes are skilfully blended - an artist too. Traditional techniques - modern technologyThis was the point at which our second assumption - that we would be seeing a very traditional approach to production - was proved wrong. Our tour of the first of Monsieur Bergeronneau’s two caveaux was a real eye-opener.  The bunches of grapes arrive in plastic baskets (not the traditional wicker ones) and go straight into the press - not the traditional wooden cylinder with a steel screw to apply pressure from above, but a gleaming stainless steel one that would have been more at home in an oil refinery. Monsieur Bergeronneau explained proudly that his was the first 8000-kilogram press in France to be built entirely of stainless steel. The grapes, still on their stalks to keep open channels for the easy escape of the juice, are loaded through hatches like those on a tanker-lorry. These are bolted down, and a membrane bag is inflated with compressed air, gradually forcing the grapes to one end of the cylinder. When 4000 litres of juice have been extracted, an automatic system stops the compressor to enforce the next INAO regulation. This allows a total of 5000 litres of juice to be taken from each 8000kg batch, but in three separate batches. The 4000 litres of first-run juice, called the cuvée, is of the best quality. Next come 600 litres classified as the premier taille and then 400 litres of deuxième taille. There is plenty more juice in the grape pulp, but this cannot be used to make wine. By law, the remaining grape pulp must go to a distillery to produce marc de Champagne, the local brandy. A second electronic system employs a ’magic eye’ to monitor the colour of the juice when pressing black grapes and to stop the press as soon as the permitted limit is reached. This is much more sensitive than the human eye. Monsieur Bergeronneau assured us that all this technology has nothing to do with economy or an obsession with modernity. It really does contribute to the production of better wines. The membrane press allows very little air to come into contact with the juice, and it can handle batches of any size. ’There has been great progress in the last five years.’ The newly-pressed juice is tested for sugar-content, which will determine the final alcohol level. If necessary pure sugar can be added - something not usually permitted for French wines. Then it goes into the cuves - the closed fermentation vessels in which the yeast that lives naturally on the grapes works its first miracle, converting sweet juice into dry, alcoholic wine. A temperature of 20°C is needed for this stage. Almost all Monsieur Bergeronneau’s cuves are of stainless steel, though he has a few older mild-steel ones which make good wine but require much more maintenance to avoid rusting.  The largest cuves hold 20,000 litres of juice, but smaller ones of 10,000, 5000, 2000, 1200 and 1000 litres allow the flexibility of the press to be exploited to the full in producing small spéciales cuvées. The young, dry wine rests for some months, being pumped periodically into clean cuves - the process known as ’racking’ - to leave behind the sediment, which might otherwise contribute ’off’ flavours. Many subtle chemical reactions take place during this time, usually including one that converts sharp malic acid into more mellow lactic acid. The real artistryAt this point, most of a still-wine producer’s work has been done and the quality of the cuvée has been established. But the real work of making Champagne has just begun. In February, the assemblage (blending) is done. This requires a sensitive palate, a great deal of experience and - above all - real imagination. Tasting young, raw wines and deciding what contribution they will make to a blend that has not only matured, but has acquired both fizz and extra alcohol, is an awesome task. Monsieur Bergeronneau has a small laboratory area where he does this crucial work.  La Méthode ChampenoiseBut the true magic of Champagne-making begins when the blended wine has been bottled and dosed with liqueur de tirage - a mixture of young wine, sugar and yeast - and bottled. A small plastic pot is inserted in the neck of each bottle before it is sealed with a steel crown-stopper like those used on beer bottles. The bottles are stacked on their sides in cool cellars (9-12°C) and left for at least 60 days, during which time a slow second fermentation produces the famous fizz and raises the alcohol content by about 1%. Their miraculous work done, the yeast cells die and settle very slowly to form a sediment - the ’lees’. This is gradually broken down by enzymes in a process called ’autolysis’ that can change the quality of a Champagne greatly - for better or worse. Only experience enables the wine-maker to judge how long to leave the wine and exploit this process successfully. Some very special wines are left on their lees for five years or more. Much Bergeronneau Champagne spends this period in the old cellar taken over from Florent’s father, François. This gloomy brick vault was stacked with around 40,000 bottles when we visited, though it will hold as many as 60,000. (Épernay and Reims boast 100 kilometres of these subterranean tunnels, through which visitors can travel on a small train.) The sediment is the central problem of Champagne production. The gas pressure in the bottle is now between five and six atmospheres, and we all know how a bottle of bubbly can erupt if it is opened carelessly. So how do you get all the sediment out but retain the gas, without which it would not be Champagne? IOne false move will throw up a cloud of fine particles that takes months to settle again. The legendary ’inventor’ of Champagne, the blind monk Dom Pérignon (born in 1639 and commemorated in Moët & Chandon’s prestige brand), stored his bottles upside-down in sand so that the sediment settled on the bottom of the cork. A skilled sommellier (wine waiter) could ensure that it was all blown out when the bottle was uncorked - the process know as dégorgement - without losing too much of the precious wine. Later, this was done in the cellar and the bottles were topped up and re-corked, but it was still very difficult to avoid clouding the wine. In 1884 the technique of freezing the sediment in the neck of the bottle was introduced, allowing it to be ejected as a solid plug. This not only solved the main problem but, because a cold liquid holds more gas in solution than a warmer one, it incidentally preserved more of the fizz.  Apart from other shortcomings, this technique presented prodigious storage problems. A second legendary figure, the widow Nicole-Barbe Clicquot - la Veuve Clicquot of the famous orange label - developed the process of remuage. This allowed the bottles to be stacked compactly on their sides throughout the long period of secondary fermentation before they were inserted for a relatively short time into holes in wooden boards known as pupitres the same word we learned in school French lessons to describe our desks). There they were gradually tilted to a vertical position with a succession of deft twists that loosened the yeast from the glass without throwing up a cloud, allowing it to move down the neck. This is how it is done to this day, though mostly by machines.  Monsieur Bergeronneau has such a machine - not ’state-of-the-art’, he told us, but very practical. The bottles are held in iron cradles and a complicated system of gears and chains does the remuage automatically. However, larger bottles - magnums (1½ litres) and jeroboams (3 litres) - are still dealt with by hand. When all the sediment has collected in the little plastic pot under the crown stopper, the necks of the bottles are frozen and the pots are removed in the process of dégorgement à la glace. The wine is sniffed critically to check its quality and then the bottle is topped-up with liqueur d’expédition - more of the same wine sweetened as required with sugar, which will not be converted to alcohol because no live yeast is present (we hope!). Finally, the stopper is replaced by the traditional wired-on cork. This is the only stage in the process that Monsieur Bergeronneau does not do in-house: a sub-contractor brings his expensive equipment to the caveau, disgorging 8000 bottles a day. The finished bottles are now stored for the final maturation - a period that differs for each cuvée - and only when they are ready for dispatch, weeks, months or years later, are they washed, labelled and capsuled.  The winesThe fruits of all this skilled and loving endeavour are seen in the current range of eight Bergeronneau Champagnes. If you want to buy them - and enjoy a dégustation before choosing - you should make an appointment by phone (03 26 49 75 26) or fax (03 26 49 20 85). The basic Brut and Demi-sec cost 73 francs a bottle and 45 francs a half-bottle. The Extra-brut is 75 francs. The Brut Grande Réserve is available in half-bottles at 48 francs, bottles at 77 francs, magnums (two bottles) at 178 francs and jeroboams (four bottles) at 430 francs. One of these whoppers made a spectacular pop for us at midnight on Millennium Eve! Brut Rosé costs 80 francs a bottle, and Cuvée Saint-Lié (named after the beautiful local chapel and still sold under the name of Florent’s father François Bergeronneau) is 86 francs. The real surprise is the Brut Millesimé 1988. Champagne producers only make vintage wines - those blended entirely from the wines of a single year - when that year produces exceptional grapes. Having just drunk a well-chilled bottle of this wine with some good smoked salmon, we can state categorically that it is a real bargain at 108 francs - around £10. Finally, when we visited, there was the Cuvée de l’An 2000, produced specially for the Millennium, at 90 francs. The screen-printed bottle made a splendid souvenir for this very special occasion. We solved most of our 1999 Christmas shopping problems by buying a bottle for everyone, to be parcelled with a kit from the Lakeland catalogue which turned the empty bottle into an attractive oil lamp. Having tried all the Bergeronneau bubblies, we would be happy to drink the Brut Grande Réserve at around £7.50 a bottle on all but the very grandest occasions.

|

Personal site for Paul Marsden: frustrated writer; experimental cook and all-round foodie; amateur wine-importer; former copywriter and press-officer; former teacher, teacher-trainer, educational software developer and documenter; still a professional web-developer but mostly retired. This site was transferred in June 2005 to the Sites4Doctors Site Management System, and has been developed and maintained there ever since.

|

|